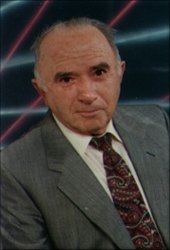

From a young age, Prof. Yeshaya Yarnitsky stood out as a nonconformist. His creative life led him to a unique combination of research and education and to an unprecedented contribution to the diamond and gemstone industry. Alongside these, his radiant and loving personality was always clear

The film, This Is My Life, produced by the family in 2009 for Prof. Yeshaya Yarnitsky on the occasion of his 80th birthday, opens with the singing of happy birthday with him sitting in the backyard surrounded by his grandchildren. This moving family picture reveals only a sliver of the full and rich life and the contribution and work of its main character. Later in the film, a fascinating life story is revealed of a loving man full of joie de vivre.

He was born in 1928 to Zionist parents who immigrated to Israel from Poland after World War I. His father, who came from a family of industrialists, took a job in the railway factories in Haifa; his mother was a homemaker. “My father grew up in a difficult period,” says his daughter Dafna, “they lived on Sirkin Street, on the border between the Jewish Hadar Hacarmel neighborhood and the lower city, and the family waged a daily struggle to make ends meet and security. That was the period of the Arab Revolt, and according to his stories they would sleep with a knife under their pillow and lived in constant fear.”

Having come into the world after an eldest daughter and with four sisters born after him, Yarnitsky’s parents aspired for their son to advance in religious education and become a stellar Torah student and in the rabbinate. However, young Yarnitsky was quite mischievous and felt out of place in religious education. In addition, he showed impressive technical abilities in taking apart and reassembling everything possible, which led his father, towards the fifth grade, to enroll him in the Hebrew Reali School of Haifa. “In doing so,” Prof. Yarnitsky said in an interview with him in 2015, “my father told me that he believed that I would never become a rabbi, but that he hoped that at least I would become a mensch. And so it was.”

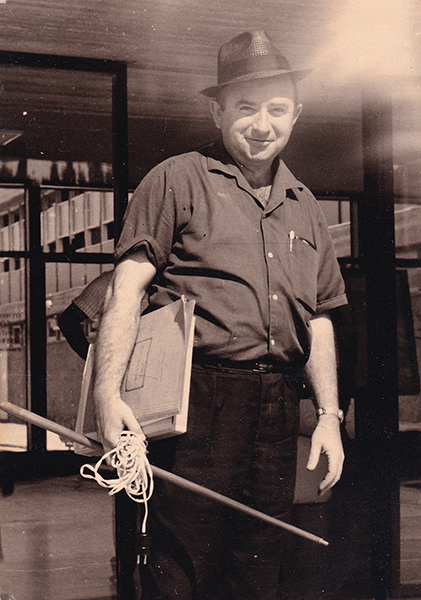

Yarnitsky’s playfulness did not stop even when he was a student at the Reali School; but it was there that he finally found a home for his natural curiosity and diligence. “The Reali School opened a wide door to the whole world for me,” he said, “and although I lacked the knowledge required to complete all subjects, I took the task upon myself and acquired that knowledge with endless dedication. I turned the school library into a home where I spent days and nights.”

Among the Books at the Reali School

The ability to spend hours in the library and study alone became a formative experience for Yarnitsky. In This Is My Life, Yarnitsky returns to the corridors of the Reali School and enters one of the classrooms. “This school shaped my spirit of learning and my willingness to sacrifice, seek, be curious, learn on my own,” he tells the young students before him. He especially loved Bible lessons taught by his revered teacher, Dr. Arthur Biram, the founder of the Reali School to whom Yarnitsky was always grateful.

His love for the Book of Books never did cease. As a creative, original-thinking person, he incorporated the love of the Bible into the fabric of his life, even when he was already a successful scholar. Among other things, for years he led a weekly Talmud lesson for a group of Technion faculty members, mostly secular, who found the subject close to their hearts. Towards the end of his life, he expanded the scope of his work in the field and published two series of books on weekly Torah portions. Another aspect of his work with Jewish sources was his painting, which he discovered after retirement. With the help of painter and teacher Baruch Elichai, Yarnitsky discovered an entire world of expression and creativity in painting and developed a creative and unique technique for painting on wooden boards with his fingers. The hundreds of paintings he left, many of them dealing with stories of the Bible and Judaica, some of which were displayed in exhibitions, were another expression of his love of the Bible, which was rooted in his days at the Reali School.

The Reali School also ignited Yarnitsky’s sense of social involvement. During the last three years of his studies at the school, he founded and led a branch of the pioneering youth movement Mizrahi Youth, which later merged with Bnei Akiva. From that time, and throughout his whole life, Yarnitsky devoted much of his time to public activities for the benefit of society and the community. Among other things, he was for many years a member of the Haifa City Council and a member of several municipal committees. Ranging from education to the environment, his work in the municipal framework left its mark on the quality of life of the city’s residents. He also received the Beloved of Haifa medal in 2004. His extensive work for society at large includes the establishment of the Western Galilee Education Campus in Ma’a lot in the 1970s, his contribution to the Joint’s Livelihood with Dignity project that enables ultra-orthodox men studying in seminaries to train in technological subjects, his help in establishing Ariel University, and more.

The Gospel that Drives Action

Towards the end of his studies at the Reali School, Dr. Biram offered Yarnitsky a generous scholarship to study the Bible at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, after which he would return to teach at the school. Yarnitsky, however, followed his heart and enrolled in a bachelor’s degree program at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering at the Technion. During his studies, he met and married Esther, and they had three children. He graduated summa cum laude and accepted a job offer from the Science Corps (which later became Rafael). There he joined the late Moshe Epstein, who became Rafael’s chief rocket designer, in a project to develop a liquid-fueled rocket considered the predecessor of the Arrow missile. Upon completion of the project in 1958, he returned to the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering for his master’s degree and doctorate. In 1961, before completing his doctorate, he was hired as a full faculty member, where he led machine design and processing processes, which he defined at the time as “the gospel that drives action.”

“When I asked to set up a laboratory for processing processes and was refused,” Prof. Yarnitsky said of his early days at the Faculty, “I realized that I had to take matters into my own hands and do it myself. I borrowed a pickup truck from Rafael and took equipment and some other systems from defense industries. I adopted this approach of taking care of things myself from that point and throughout my career at the Technion.”

“Yarnitsky’s creativity was one of his most salient characteristics,” says his colleague from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Prof. Avraham Shitzer. “Even in the Science Corps, he was a star and did very creative things, and later, when he was among the first doctoral students of the Faculty, he brought his penchant for industry and did very innovative things. The mid-1960s was a time of revolution at the Technion, which switched from a German-European tradition to an American tradition that places more emphasis on research. With his creativity, Yarnitsky found the areas that suited his preferences so as not to be left out.”

“My father didn’t follow the standard academic track of laboratory work and publishing articles,” recalls his son Ariel, himself a Technion graduate and successful high-tech entrepreneur. “He was always looking for what would benefit the industry. He was an inventor at every level. I remember a large drawing desk in his office, and how he put thought to immediately solving every technical problem that was brought to him. He once told me that there is no greater joy than the joy of creation. This tendency did cost him a promotion, as his career advancement was slower. On the other hand, he got to go where his heart took him, and that’s how he got to the gemstone and diamond industry.”

“My work at the Technion filled my time, but I had a burning desire to contribute to industry and looked for research topics that would benefit industry in Israel,” Yarnitsky described his choice to deal with gemstones and diamonds. With his keen senses, he identified in these two industries the possibility of making a leap forward in production and processing and decided to invest his time in research and development. Among other things, throughout those years he developed production machines for the gemstone industry and stone processing technologies: fast mining, mechanized chiseling, fission, polishing and more.

Perfect Polish

Volumes could be written to describe Prof. Yarnitsky’s contribution to the Israeli and global diamond industry, for which he was awarded the Diamond Industry Award in 1998 by the Israeli Diamond Industry. In 1964, he established the Diamond Research Laboratory at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and another laboratory in Ramat Gan. The two laboratories were the foundation for the establishment of the Israel Diamond Institute in 1967, where he served as Chief Scientist from 1970 to 1981. He developed innovative machines for perfect and precise diamond polishing. One of the first, a rondist faceting machine he named Daphne after his daughter, revolutionized the industry. In doing so, Yarnitsky directly contributed to putting Israel at the top of the global diamond industry.

“It was an industry that required a great deal of manpower,” says Prof. Shitzer, “and Yarnitsky wanted to industrialize and streamline it. He wanted to turn manual polishing work into an automated process that would render the same qualities an excellent human polisher would. This was at the core of his career. Later, when laser technology emerged, he developed a laser-based method of looking at the stone from all angles to maximize its utilization. This is another example of his creativity and how he did not get bogged down but grew with technology.”

In 1981, after losing his wife and marrying his second wife Chana, Prof. Yarnitsky took a two-year sabbatical in Johannesburg, South Africa, which he devoted to research in diamond processing. He built a laboratory and wrote articles that were later included in the five volumes of his book on diamond processing.

Upon his return from South Africa, he continued teaching at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, training the future generation of the diamond industry. His teaching was characterized by a unique combination of advanced engineering theories and practical and applied aspects. “Professionally, Yarnitsky had an exceptional command of the subject matter, and at the same time he had radiant, respectful and loving personality. He was very respectful of the students, always attentive to their needs and questions, and willing to give them all the time they needed. They in turn appreciated him very much,” adds Prof. Shitzer.

“My father was a serial outstanding lecturer,” recalls his son, Prof. David Yarnitsky, now head of the Neurology Department at Rambam Hospital and a faculty member at the Technion’s Faculty of Medicine. “The students kept in touch with him for many years. To this day, people will come to my clinic and say, ‘Are you the son of…?,’ and tells me something about him.” In a 2015 interview, Prof. Yarnitsky concluded, “My thousands of students are the most irrefutable testament of my uncompromising love for engineering and people. The generations of engineers and practical engineers I had the privilege of educating now hold key positions throughout the industry in Israel and abroad, and I couldn’t be prouder of their success and achievements.”

A Very Giving Person

Alongside his enormous contribution to academia and industry, Prof. Yarnitsky stood out for his concern for others. “There was always someone that dad took care of, whether with financial help, or helping them find a job so they could make a decent living, and certainly with good advice and sincere interest. He wouldn’t relax until he managed to sort out the problems and solve the difficulties,” says his daughter Dafna. His friend Prof. Avraham Shitzer adds, “Yeshaya was like a ‘social welfare office’ for the people he brought to his lab, always caring for them and looking for ways to help them integrate into the industry. He was also always doing good deeds in the Jewish sense of the word: charity, support for widows, assistance to needy families, and even matchmaking and collecting money for weddings. He had a pleasant manner in everything he did. He was a man of an unconditional and limitless capacity for giving, in all areas. There aren’t many people like him.”

“Personally,” adds Prof. Shitzer, “I miss him very much. When I pass by his office, I feel a twinge in my heart. He liked conversation, was very open, always willing to hear opinions other than his own, to put things on the table and speak in a friendly manner even about cardinal questions related to religion and faith. On the one hand, he was a polymath, a man with extraordinary abilities and modest both in appearance and in his desires.”

At the end of the film, Yarnitsky is seen again with the grandchildren, helping them pick lemons from the tree in the backyard while humming the song a children’s song, and then instructing them how to draw with their hands. In the background, we hear his voice saying, “It’s good for a person to see their offspring. It’s a feeling that everything is good, that everything goes on. I look back at my 80 years and see that I didn’t waste my life, but met people, raised people, and the most important thing I learned was that there is no challenge that can’t be overcome. If you have a vision, you can achieve it, and you should never give up.”