Self-taught, curious, a true Renaissance man, philosopher, pioneer, mentor, Zionist – this is how Prof. Simon Braun’s colleagues and family describe the man whose life story and character connected countries, fields of expertise, and people, and whose life concluded with his following words: “I lived a happy life.”

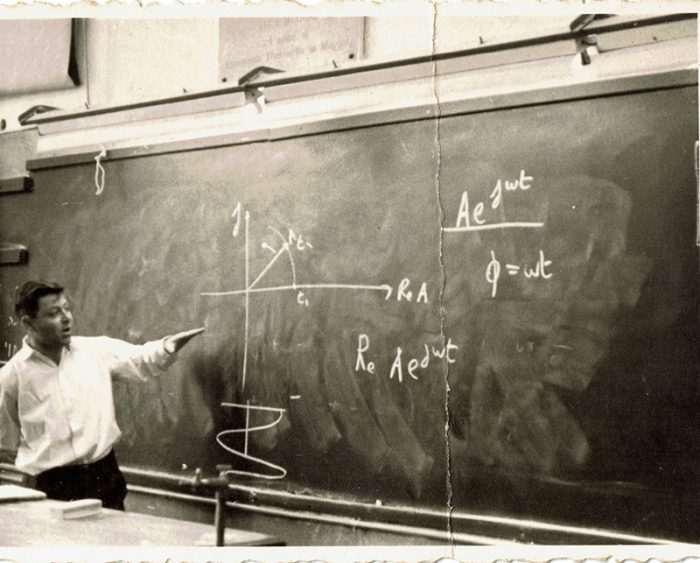

In 1959, the then Dean of the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering at the Technion, Prof. Ehrenreich, invited the young Simon Braun to transfer from the Faculty of Electronic Engineering where he had completed his bachelor’s degree with honors to do a master’s degree in his faculty saying, “I have a feeling that you are capable of leading the Faculty into new horizons, though I do not yet know what they are.” The professor seemed to have identified Simon Braun’s unique core trait – his relentless curiosity and creativity that brought together fields and applications.

Writing about the late Prof. Simon Braun is a complex task. Should we focus on his many academic and research achievements? On his creativity and unique ability to connect different fields and disciplines? On the famous newspaper he founded and edited for 35 years? Or perhaps on tracing and understanding the path he took from his wanderings throughout Europe as a child during the Holocaust to becoming a groundbreaking researcher with an international reputation? And what about his being a lover and expert in art, music and photography?

Braun was a polymath. According to Wikipedia: “A polymath is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems,” just like Simon Braun.

Prof. Braun’s rich legacy includes laying the foundation for recognizing signal processing as an integral part of many mechanical engineering disciplines, which resulted in major improvements in reliability, efficiency and safety in a variety of engineering fields. In addition to numerous articles, his important contributions include influential textbooks, the Encyclopedia of Vibrations, for which he was editor in chief of its three volumes, and the Journal of Mechanical System and Signal Processing, which he founded and edited for 35 years and remains to this day prominent and internationally renowned journal.

He founded two chairs of which he was very proud. The first was the Raoul Wallenberg Chair, named after the Swedish diplomat who saved Jews during the Holocaust and ended paying for it with his life. Prof. Braun saw in it a sort of closure. And the second was the Dan Tolkovsky Chair, in honor of the legendary commander of the Israeli Air Force and one of the founders of the Israeli high-tech industry.

In addition, and probably his most important achievement, was the creation and consolidation of an ever-growing international community of professionals, students and professors in the interdisciplinary field of mechanical, electronic, and computer engineering, with which they became acquainted, directly or indirectly, through Prof. Braun himself.

Childhood in the Shadow of War

Prof. Braun’s life is seen in a different and new light when learning about his history and early years. He was born in 1933 in Vienna, but used to count his age starting in 1945, the year he arrived in Israel. One of the earliest memories he told his wife and daughters about was Kristallnacht on November 9-10, 1938, when the city’s main synagogue, where his father had served as cantor, was destroyed. From that night, young Simon’s life was destined to change completely. Throughout the war years he was smuggled with strangers and hidden throughout Europe – from Austria, through Germany, France, and Italy to Switzerland. In each country he was given a different name and a new language. In each country he learned how to take care of himself better and manage on his own.

At the end of the war, witnessing the devastation of Europe, Braun, who was only 12 years old, decided to immigrate to Pre-State Israel. He joined Meteora, the first ship to transport child Holocaust survivors to Israel. As soon as they reached the shores of Israel, the children were apprehended by the British and placed in a detention camp in Atlit. Surprisingly, not long after, Simon’s parents also arrived at the detention camp, where he saw them again, but he could not immediately reunite and live with them.

He actually only began his formal education when he was 13 years old, but by then he was already an autodidact who had taught himself to read and write at the age of four and learned the languages of the countries where he had hidden. Later, in Pre-State Israel, when he was transferred from the detention camp to a religious boarding school in Kfar Hasidim and was forbidden to write on the Sabbath, he taught himself to do all the mathematical operations in his head. Perhaps it was then that his unique connection to science and engineering began, as well as the realization that he had phenomenal learning skills. Braun later moved in with his parents in the Carmel area of Haifa and studied at Professional High School for Certified Practical Engineers and Technicians. The family led a modest life, with Simon helping to make ends meet by distributing bread every day early in the morning, before starting school.

When the State of Israel was established and upon completing high school and receiving his engineering certificate, Braun enlisted in the IDF, where he was one of the founders of the Signal Corps’ mobile laboratory. In parallel with his military service, and thanks to his autodidactic skills, he completed a bachelor’s degree in engineering at the British University Institute of Engineering. Upon completion of his service, he enrolled in another bachelor’s degree program in electronic engineering, this time at the Technion.

Proud Zionist

He completed his master’s degree and doctorate at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and as a student was given the tenured position of senior lecturer. “As a proud Zionist,” says Mira, his widow, who married him when he was a student, “it extremely important to him to complete his studies in Israel. When the time came for a postdoc, despite the strong recommendations of his colleagues that he had to go to the United States otherwise it would be problematic from a professional and academic point of view, he refused to leave his sick parents and completed his postdoctorate in Israel.”

This story embodies what characterized Prof. Braun throughout his personal and academic life: despite the decision he made when he arrived in Pre-State Israel to put the past behind him, that past remained with him as a compass. First, as a very loving and devoted family man to his wife and three daughters despite having been deprived of his own childhood years. Second, his deep connection to Israel. His wife Mira tells how over the years, when he lectured abroad, he always went as a representative and explainer of the country. “We established ties with Jewish and non-Jewish communities abroad. We introduced Israel to people who did not know about it in churches and in other venues. For the sake of public relations, Simon overcame his aversion to churches and appeared there,” she wrote in his obituary.

Prof. Braun insisted on designing the logo of the newspaper he founded, which reached one of the highest ratings in the world, in blue and white, to show that it was ‘made in Israel.’ He also worried about the future – in the will he left to his grandchildren, he asked them not to leave the country.

Prof. Braun’s international career and the variety of subjects he addressed, researched and worked in can be described as extraordinary: he worked in medical engineering with the best researchers in Israel and published a paper with Prof. Rafi Beyar documenting his success in measuring an increase in stress levels. He founded a newspaper, organized conferences, and conducted courses and workshops around the world to study and research the field he had established. He developed standards for systems protection, among them is the Bank of Israel’s security system. He served as chief scientist in the Israel Police and the Forensics Department, developed curricula in technology, mathematics and physics to improve learning and teaching at the Ministry of Education, was the first Western scientist invited to Taiwan and China, even before they established diplomatic relations with Israel, and worked at research institutes in the United States such as Ford and General Electric.

Understanding Things in Depth

At the same time, Braun developed a special love of photography, which became one of his greatest passions later in life, as well as art and music. He was also a journalist for the French cultural newspaper La Critique Parisienne.

Everyone who wrote or was interviewed about Prof. Simon Braum noted in particular his precision and modesty and his tireless curiosity. “What motivated him was the desire to understand things in depth,” says Prof. Moshe Shpitalni. “And it was like that for the rest of his life. In the two years before his death, a new subject called Deep Learning became the new hot topic. One day, I met Simon by chance at the beach and told him about it. I had a feeling that it would interest him. He did find it interesting and began to learn it, wanting to understand. He researched the literature and people and was deeply interested in image analysis. He used to say, ‘I have to figure out how it works.'”

“Simon was a philosopher,” says his colleague Prof. Yoram Halevi. “As a researcher, he was as quick as a flash, very sharp, always thinking and going faster than anyone. In addition, his uniqueness was that his vision of things was broad and deep and led to creative and nonstandard combinations of fields. Therefore, he was also a pioneer and innovator, with the knowledge and courage to connect things. He searched for interesting things and where he could contribute and promote the most. All of these were a great inspiration to me. I consider him a mentor.”

This rich and tireless work is perhaps the background or path leading to the phrase Prof. Simon Braun asked to engrave on his tombstone: “I lived a happy life.”