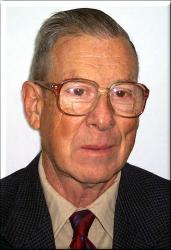

Prof. David Pessen immigrated to Israel from the United States and joined the Faculty in 1955. Over the years, he taught control and automation and stood out for his quiet and modest character. A collection of biographical notes he wrote with great wit and humor after his retirement reveals the events that shaped his life

In the introduction to his biographical notes, Pictures from My Life (1999), Prof. Pessen wrote, “Many psychologists claim that the name given to a child can influence the course of their life and character. If that’s true, I’m in trouble, because the name Wolfgang given to me at birth was only one of five names I was destined to carry during my lifetime.”

The psychologists quoted in that biographical passage were probably right to some extent because the changes in Pessen’s name described later in the passage and those that followed, were due to his life circumstances, which changed, sometimes dramatically, certainly shaping his unique personality, as his colleagues at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering attested to years later.

He was born in 1925 in Berlin, the second son of a family of three children. His father had come to Berlin from East Prussia, and worked as a librarian at the Jewish Community Library in Berlin, which he also managed. His mother was a native of Berlin. The family lived the bourgeois life of the city’s Jews in the years before the Nazis came to power, which was characterized by preserving Jewish tradition while assimilating into German culture.

Things began to change in 1933. The family experienced a number of anti-Semitic incidents that culminated in Kristallnacht in November 1938. In 1936, young David was transferred from the Catholic school where he studied to a Jewish school called Zikel, of which he had many memories. After Kristallnacht, the Pessens realized they had to find a way out of Germany. They applied for a visa at the US Consulate but their place in line was so low that it was clear they would have to wait a long time. One of the passages in the biographical collection describes what finally happened. “My father died in February 1939 and my mother was frantically searching for ways to get us out of Germany. Then the unexpected happened – like Deus Ex Machina at the opera. My father had a wealthy uncle in South Africa who offered to deposit enough money in an English bank to enable us to stay in England until we got the visas to the United States, without becoming a burden on the British taxpayer. So we got a British transit visa under the condition that we would not be employed for wages in England, so that we would not increase their high unemployment rates.”

Berlin, Manchester, New York, Philadelphia

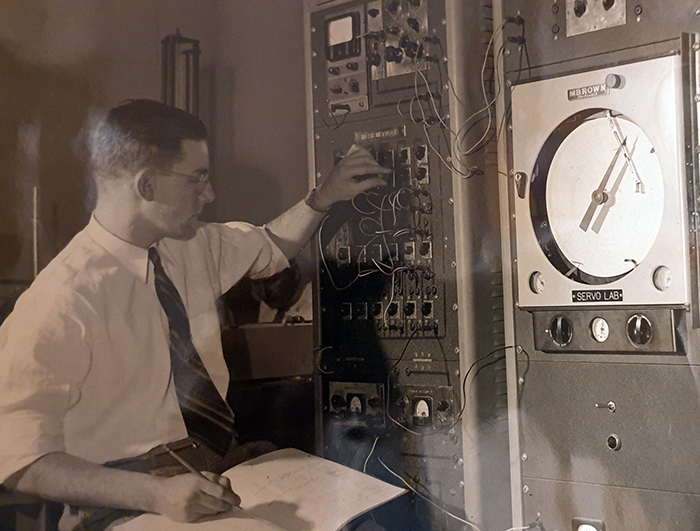

The family lived in Manchester, England, for a little over a year, during which time Pessen attended school and managed to get a job as a pharmacist’s assistant. Finally, the long-awaited visas arrived, and in September 1940 they sailed from Glasgow to New York, and from there to Philadelphia, where his mother’s brother lived. They lived in crowded conditions, three families in one house, and later in more spacious rooms as their situation improved. In his 15 years in the United States, David Pessen finished high school at an early age, began studying mechanical engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, enlisted in the US Navy, and was discharged when the war ended, just before he was sent to serve in the Pacific. Upon his discharge, Pessen returned to his engineering studies at the university, completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees (1950), and began working in the Research and Development Department of Brown Instruments, a division of Honeywell Corporation, in the field of automatic control systems. In fact, he was involved in this field all his life, including during his academic career.

While studying at university, Pessen joined an organization of Jewish students and met a charismatic representative of the Jewish Agency, about whom he wrote, “The shaliach did a good job of brainwashing us with the idea that aliyah (immigration) to Israel was the right thing to do. So I filled out a form outlining my skills and sent it to the Jewish Agency in Israel. A few months later, I received a letter from the Technion offering me a position as a lecturer in mechanical engineering. At that time, I didn’t really intend to make aliyah, but I decided to come for a two-year trial.” The collection of documents kept in his home and scanned by his family includes the letter from Technion President Yaakov Dori dated October 1954, notifying Pessen of his acceptance as a lecturer and detailing his employment arrangements at the institution.

Regarding the circumstances of his immigration to Israel, his son Noam adds, “Once we saw the movie Brighton Beach Memoirs together. It describes a Jewish family from Brooklyn on the eve of the outbreak of World War II from the perspective of a 15-year-old boy. My father said that the film was similar to what they experienced, living in crowded conditions with relatives. His sister also told me about the tension that existed in that shared home, and I assume that was one of the reasons he decided to come to Israel.”

Pessen arrived in Israel in 1955, settled in Haifa, and after six months of studying Hebrew in an ulpan, began teaching at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering at the Technion. A few years later, he married his wife Liora, whom he met at a chamber concert held at the home of Prof. Stefan Stricker of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering. Pessen wrote about this in his memoirs. “Among the guests at Prof. Stricker’s home were Prof. Karl Stark and his daughter Liora. I was very impressed with Liora, especially by her interest in chamber music, which was not everyone’s cup of tea… Only many years later did Liora confess to me that she didn’t really like chamber music and had only come to accompany her father instead of her mother, who wasn’t feeling well that evening.”

While working as faculty member, Pessen completed his studies, and in 1962 received his PhD in mechanical engineering.

Tidy Yellow Sheets of Paper

Someone who knew Prof. Pessen during the first years at the Faculty was Prof. Zalman Palmor, who later became his colleague. “I came to the Faculty as an academic reserve soldier in 1962,” says Prof. Palmor, and continues, “The Faculty was then in transition between the ‘founding generation,’ which were mainly engineers who had come from Germany, and the generation that succeeded them, mostly young scientists educated in the United States. Those were two completely different schools of thought. I remember that in my third year of studies, Prof. Pessen came to teach feedback and control systems, a subject that was innovative at the time, certainly at the Faculty. His course fascinated me and opened the world of control to me. In fact, it lit the spark I had the area of expertise I specialized in until my doctorate. Later, when I became a faculty member, we built a control research group that was considered one of the best in the world, and it was Prof. Pessen who started it at the Faculty. He helped and supported and was a partner in building the infrastructure.”

“Even as lecturer he didn’t fit the pattern in the Faculty’s landscape. He was quiet and very modest, profound, didactic and tidy, a real Yekke (Jew of German-speaking origin considered to be quite pedantic, and with the culture of the eastern United States,” recalls Prof. Palmor. “He would come to class with densely written yellow sheets of paper and teach from them, and you could see that the pages were super neat with everything cleverly laid out. He came to the Faculty with practical experience in the industry, and at that time was also busy building laboratories in his areas of expertise, many of which he built with his own hands, which he enjoyed very much. He always did everything modestly, without pushing.”

His colleague Prof. Yehoshua Dayan also remembers Prof. Pessen from his early days at the Faculty. “Prof. Pessen welcomed me to the Faculty when I arrived in 1971 as a young lecturer on control issues. Thanks to his help and support, I was able to integrate into teaching and research at the Faculty, even though my previous training was in chemical engineering. With his assistance and backing, I also taught kinematics of mechanisms, a distinct subject of mechanical engineering. Later on, we taught control together, and together advanced the field of control in terms of the laboratories as well. Prof. Pessen built the advanced laboratory on his own, except perhaps a single exercise, and he was the one who led it. The laboratory was always at full capacity and was in great demand from students throughout all the years he taught.”

“Dad really loved teaching,” says Noam, “including us, his children. He would answer questions didactically and patiently. Even my son, who didn’t get to know him well, remembers his good explanations. He also liked the labs very much. He had good hands and a technical sense, which, unfortunately, he did not pass on to any of his children. He would handle electrical and carpentry matters at home himself very precisely. To this day, I have all kinds of tools that I have no idea what to do with.”

For years, Prof. Pessen led control and automation studies at the Faculty. Many editions and updates of his book, Automatic Regulation, were published, and it was finally renamed Introduction to Control and Automation. The book was used not only at the Technion, but also at Tel Aviv University and Ben-Gurion University, and is still used today as a textbook in almost all engineering colleges and schools. Many of the teachers in Israel, at all levels, were enthusiastic about the book, used it and sent Prof. Pessen their comments and suggestions, which he edited and included in later editions. His book, Kinematics of Mechanisms, which he wrote with the late Prof. Arthur Shavit, also became the bible of the profession and is still used to this day.

Prof. Pessen was one of the first to bring the innovation of programmed controllers to the engineering community in his book, The Design and Application of Programmable Sequence Controllers for Automation Systems (Longman, January 1, 1979).

In 1989, his book, Industrial Automation: Circuit Design and Components, was published by Wiley & Sons. The book has received worldwide distribution and is considered the leading textbook in the field of small investment automation. It also includes chapters covering topics such as industrial pneumatics, robotics, and switching theory. In addition, topics like flexible automation, microcontrollers and programmable controllers are treated in depth, and since its publication there have been no major changes in the principles and theory presented in the book.

“David was undoubtedly a great expert in his field,” says Prof. Dayan, “He advised many companies in the industry on different matters and also specialized in patent registration. He himself had five or six American patents, and anyone who wanted to register a patent, from Technion staff or from among his former students in the industry, asked to consult with him.”

Among other things, he is remembered for his involvement in the registration of the drip-irrigation patent developed by Faculty graduate Rafi Mehudar, who later became the main asset of Netafim. “The person who actually helped Rafi Mehudar write the patent was Prof. Pessen. Rafi remembered that and kept in touch with him until the day he died. I never heard a word from David about it, which attests to his modesty,” says Prof. Palmor.

Thousands of Photos and Slides

Prof. Pessen also had many hobbies, some of which were known to his colleagues in the Faculty; others developed after his retirement. “It was impossible not to be impressed by his knowledge and understanding of music,” recalls Prof. Dayan. He and Liora had a huge record collection, some of which he gifted to me when they moved to an assisted living facility – for that I always thanked them.”

In addition, Prof. Pessen loved to travel in Israel and around the world and was a prolific amateur photographer. “When guests came from overseas, dad would always travel with them and provide guided tours around the country, demonstrating his incredible knowledge of nature, history and the Bible,” says Noam.

In addition, Pessen left behind a collection of some 7,000 slides, numbered and sorted by subject and date, including great documentation of Israel in the 1950s-1970s. In April 2020, during the COVID pandemic, his son-in-law Jonathan Stotter (son of the late Prof. Arthur Stotter (who was also a professor at the Faculty) and his grandson Alon uploaded the entire slide collection to a special website they created just for this. “He really liked holding ‘slide nights,’” adds Noam, “He would invite guests, show them slides and add explanations. When he retired, for a period of ten years until he weakened, my parents traveled the world leaving a huge number of albums with photos.” His colleague Prof. Joshua Dayan particularly remembers his trips to Sinai, when it was still under Israeli rule, safe and open for Israelis to visit. “He always came back with amazing stories and photographs,” Dayan says.

Final Thoughts

“Retirement is a great institution,” Pessen wrote toward the end of his notes, “it gives you the opportunity to do things you planned to do all your life and never had the time, like writing this collection. But the reader may be surprised to hear that I have devoted quite some time to writing a Hebrew-English-Russian dictionary, despite the fact that my knowledge of Hebrew is not very impressive and my knowledge of Russian is nonexistent.” Later in the passage, Pessen describes the circumstances of writing the dictionary. It was initially written as a Hebrew-English dictionary based on Hebrew roots and their derivatives, and he then saw fit to add translations into Russian, which would serve the many immigrants who had arrived at that time from the CIS countries. He added the translations with his Faculty colleague Dr. Yuri Kligerman.

Another text written by Prof. Pessen with the intriguing title, The Book of Levy, begins as a short story and continues as a kind of theological-cosmological-metaphysical text, in which Pessen rewrites the story of creation. “The main purpose of the text is to resolve some fundamental issues in theology that I have grappled with since leaving the Zikel School in Germany in 1939,” Pessen concludes in the penultimate chapter of his biographical collection.

In 1998, Prof. Pessen organized an exciting reunion of ten of his 27 classmates from Zikel School. It was the culmination of the attempts he had made over the years to find his classmates who, due to different circumstances, were scattered all over the world. “The fact is that we have all been quite successful professionally,” he wrote after the reunion. “Were we such geniuses? Was Zikel School such a successful institution? Or did circumstances and the pressure we were under help shape us and drive us to succeed? I think the answer lies in a combination of all of these,” he concluded.