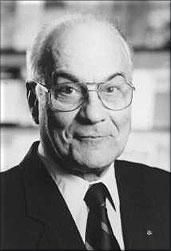

From being a child who got bored in school and didn’t finish high school, Prof. Gad Hetsroni grew to become one of the world’s leading experts in multiphase flow, and a person who valued studies and research above all. He will be remembered by the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering both for his personal dedication and concern for students.

In a radio interview with Prof. Gad Hetsroni as a nuclear energy expert, the interviewer pressed him about the safety of the nuclear reactor in Dimona. The interviewer asked a long question, cited data, detailed the dilemmas. When it was Prof. Hetsroni’s turn to answer, he said only one word: Yes.

That moment is perhaps telling about the type of person and scientist he was: no-nonsense and matter of fact, an expert and professional who did not need to prove his knowledge and stature with words, a man with an ambition to go far who did secure his reputation through politics but through deeds. And someone with a unique sense of humor.

Prof. Gad Hetsroni, one of the most prolific and brilliant among the Faculty’s scientists, a renowned international authority in his field, was born on October 10, 1934, in Haifa, the youngest of three siblings. His mother Kata was the owner of the renowned Hetsroni Gift Shop at the Hadar Foundation House, and his father Yitzhak was a carpenter.

As he later told his daughters, even as a young boy Hetsroni was interested in experiments and tried to understand how things were built and worked. He tested flows of water and soap bubbles – the world itself was a huge and intriguing laboratory for him.

In 1936, before the establishment of the State of Israel, the Great Arab Revolt broke out in Haifa. There were riots all around the city, which profoundly affected the curious boy. In 1938, when he was only four years old, his father went to work and was murdered in a severe act of terrorism that was part of the events of those years. His mother remained the sole family breadwinner and had to be away from home for long hours, during which Gad remained with his older brother. Those hours alone, either at home and on the streets, buying ice cream with the money left for them by their mother for lunch, were without a doubt what shaped Hetsroni to become independent and determined to excel and forge his own unique way in the world.

As a child, Hetsroni did not really deal well with school. He found school boring and lacking the challenges he was craving, and he made sure to express his feelings out loud. It is hard to believe, but the man who became an internationally renowned and prolific professor was expelled and moved between schools, until he was finally transferred to the agricultural boarding school in Pardes Hanna. There he did not finish high school either and enlisted in the army at the age of 16, with the approval of his mother.

From Agricultural School to a Scientific Career

However, this did not prevent him from paving a magnificent academic career for himself. His lack of success in school did not affect his confidence, skills and desire to succeed, perhaps even the opposite. He became a person who demands the most from himself and his surroundings. When it came time to decide on his path in life, Gad Hetsroni enrolled in the Faculty of Agricultural Engineering at the Technion for studies that combined his attraction to engineering with the field of agriculture he had become acquainted with and loved at boarding school.

In 1957, at the age of 23, he completed his bachelor’s degree summa cum laude, and from there, together with his future wife Ruthie, he transferred to Michigan State University to specialize in nuclear engineering; there he received his doctorate five years later. He then worked at Westinghouse as an expert on nuclear reactors and multiphase flow, subjects that had become central to his work since. In 1965, he joined the Faculty of Nuclear Engineering at the Technion. In 1971 he moved to the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, which became his home until his last day, and where he served in a variety of positions (including dean for two years), taught dozens of master’s and doctoral students, and published hundreds of articles. He was a visiting professor at many universities, including Stanford and the UC Santa Barbara, and was very active in the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), where he was appointed vice president in charge of countries outside the United States.

His daughters Anat and Yael say, “One of his most memorable phrases, which we remember until this day, was: ‘If you want to be a shoemaker – be a shoemaker. But you first must study and learn to be the best cobbler you can be.'” Education was one of the greatest values for Prof. Hetsroni. Its importance was a message he conveyed both at home and at work. In addition to being an outstanding researcher and experimenter, he taught and nurtured dozens of students and researchers.

“He also had a very special way of teaching. As young girls, we would sit with him so he would help us with our math and physics homework. He would explain and write on a piece of paper, and then ask, ‘Did you understand?’ When we said yes, he would throw away the paper and say, ‘Now do it alone,'” says his daughter Anat, who later became an expert in learning technologies, perhaps for good reason.

Personal Relationship with Students

“He may have seemed tough because he was laconic and would answer an email with a word or two, but when he loved and appreciated someone – he gave his all,” adds Prof. Shimon Haber, who first met Prof. Hetsroni as a student and later became a colleague and close friend. “I met him in the fourth year of my undergraduate studies. I was a student in his nuclear energy lab. In one class, I dared to disagree with something he said and say it wasn’t accurate. He paused for a moment, thought, and then said, ‘You’re right.’ This captivated me. He wasn’t looking for yes-men. He wanted to challenge his students minds and was very successful at that.”

He also expressed his devotion to the students by inviting them to his home. “We met his students, who came to talk to him and have dinner,” says his daughter Anat. He always answered questions from students, even those who were not his students.

“Also as a researcher who led research teams in the laboratory, he was unique. He was a professional with a tremendous ability to understand and make decisions quickly, and also provided a human point of view showing genuine personal concern for his team members,” says Prof. Haber. “He built a magnificent laboratory and managed large teams of ten people, each with their own purpose and mission. He had the ability to manage each one individually and everyone together. And personal concern was just as important to him. For example, after he retired, he ran a research group, and most of the researchers in the group were immigrants from the Soviet Union without financial backing. Gad took exceptional care of them: he knew everything about their private lives, was considerate, and invited them to his home. The research and staff were so important to him that he gave money out of his own pocket to pay them an adequate salary when the budgets were not sufficient.” Together with the Fund for Emergency Financial Support for Students that he launched and established, these are examples of Prof. Hetsroni’s generosity and contributions, which may also say something about the connection of the highly active and privileged scientist to the child who grew up without a father and wandered alone in the streets during his childhood.

His interest, expertise and prolific research in multiphase flow led him to take another unique step – founding the Journal of Multiphase Flow International. In early 1973, it was Gad Hetsroni himself who entered the office of media tycoon Robert Maxwell, then head of Pergamon Press, and persuaded him, against all odds, to publish the journal. Hetsroni, who believed in the great importance of multiphase flow, served as its editor-in-chief for many years and published many articles in it. The journal, which continues to be widespread and successful in the world to this day, undoubtedly took multiphase flow to its prominent position in engineering and science.

Gad Hetsroni’s curiosity was a driving factor – beyond his scientific curiosity, he loved to travel the world, visit and explore new places whenever he went to conferences, loved good food, wine, classical music, and especially opera. Not many people know that he loved diving and would go diving in Haifa and Atlit.

Most of all, he loved his six grandchildren. “It was hard to miss the soft, loving look in his eyes when he looked at them, listened to them. He made sure to keep in touch with and meet them a lot, but above all, we would talk to him every day, and in every conversation, he would go through the entire list of grandchildren and ask how each and every one was doing,” his daughters say.

Passion and Love for the Profession

His ambition and desire to advance and excel were manifested in the smallest mundane things – Prof. Hetsroni was known for opening the gates of the Technion in the morning, swimming in the Technion pool, and working until late in the evening. He considered the Technion his home away from home in every respect. His passion and love for the profession and his fruitful work as a researcher and teacher guided him almost to his last day, March 15, 2015, when he passed away at the age of 80.

“Just two days before he passed away, I came to visit him with one of my sons,” says Anat. “Before we parted – a farewell that in retrospect was the last – he told me with sparkling eyes about a new device he had bought for the lab. Then he also asked me to look after my sister.”